Intra-ASEAN Maritime Security: Interview with Dr. Collin Koh

Dr. Collin Koh Swee Lean is a Research Fellow at the Maritime Security Programme, part of the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, a constituent unit of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). Dr Koh’s primary research areas lie in naval affairs within the Asia-Pacific region, particularly in South East Asia, with a focus on naval modernisation issues. Other key areas of expertise include naval arms control, confidence and security-building measures at sea, offence-defence theory, concept of non-provocative defence, and nuclear energy development in South East Asia.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

In August 2016, the Warwick ASEAN Conference Research (Content) team interviewed Dr Collin Koh Swee Lean on recent issues regarding maritime security in ASEAN, and in particular, China-U.S. relations concerning the South China Sea. We have summarised Dr Koh’s responses below.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

1. What are the possible challenges you envision ASEAN would face when trying to promote regional cooperation in maritime security?

The first challenge is to do with threat perceptions. We need to understand that Southeast Asia is a diverse one made up many countries each with its peculiar set of national context, affecting the threats they face, the domestic and external circumstances, and the varying resource capacities that shape policy priorities. Hence, cooperation would only be possible if there is geographical contiguity and a common threat. One example is the Malacca Straits Patrols, which came about because the littoral states – Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and later Thailand – share the same strategic waterway and common perceptions regarding the economic and geopolitical fallout from not being able to police it properly.

The second challenge is to do with the lingering, residual lack of trust that was the result of history, which constrained the extent of maritime security cooperation. And of course, the overarching concern about preserving one’s territorial integrity and national sovereignty. This factor could limit the way by which Southeast Asian maritime forces engage in collaborative activities (e.g. patrols – coordinated rather than joint, since each country would not want its own forces to fall under the command of another in a “joint” framework). “Hot pursuit” of seaborne criminals beyond one’s territorial waters and into a neighbour’s could be problematic as well. But my knowledge of actual events taking place on the ground is that such “rules” were not always followed, since the maritime forces are familiar with one another that there is already a degree of operational-level trust. However, political considerations ultimately trump such operational gains, thereby limiting how far those forces could cooperate. No country in Southeast Asia wishes to be viewed as being incapable of policing its own waters; allowing another country to interfere in its waters can potentially pose a problem about political legitimacy back home.

The third challenge is certainly resource constraints. Without the requisite physical capabilities to contribute, the extent to which the country can participate and the amount of say it has is limited. And frankly, there is the issue of “face” in operation here too. I can give the example of the Philippines. Prior to taking delivery of ex-American Hamilton class cutters, the Philippine Navy did not send warships to multinational exercises because none of the existing assets in the fleet, mostly World War Two-vintage ships with dubious operational status (and which could have contrasted quite starkly with the modern, spanking new ships other countries send to the events), could undertake sustained voyages even to neighbourhood waters.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

2. Why do you think ASEAN tensions are manifesting themselves specifically in the maritime domain, and what do you think the most important triggers are for maritime conflict?

This stems from a combination of history, politics and geography. Many existing maritime disputes have resulted from newly independent countries inheriting those territories and the adjacent waters from their colonial masters, creating overlapping maritime boundaries and jurisdiction. Moreover, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS), promulgated in 1982 and subsequently ratified in the 1990s, made “drawing fences” more complex. This is because when a country seeks to assert their rights to those maritime entitlements, neighbouring countries may make claims to the same body of water based on the same legal provisions of UNCLOS, but in combination with their own historical legacies.

Southeast Asia littorals are characterised by semi-enclosed seas creating avenues for overlapping waters, porous boundaries, etc. However, under UNCLOS, coastal states in semi-enclosed seas have an obligation to cooperate. As highlighted earlier, ASEAN member states have demonstrated the ability to cooperate, if not always effectively. The present South China Sea dispute is partly a manifestation of this combination of factors – a semi-enclosed water body, history, political and legal considerations.

The nexus between geopolitical disputes and human security is a notable trigger of maritime conflict. Human security (more commonly referred to as non-traditional security) encompasses such topical issues as food security and energy security. These are not stand-alone issues since they are strongly linked to geopolitical disputes which are considered “traditional”. For example, the present South China Sea disputes are related to food security. The rising affluence of the coastal communities and growing importance of harvesting marine fishery resources for socioeconomic development drive fishery competition in the South China Sea, exacerbating present conflict, and the potential threat and use of force by coastguards and navies against fishermen.

The rise of domestic nationalism has altered strategic calculations of governments in the age of “public diplomacy”, pressuring them to adopt undesirable policies to mollify public opinion back home and to strengthen their political legitimacy. Countries may ride on domestic nationalism, based on protecting national prestige against a perceived affront by a foreign, rival government, or “externalizing” domestic problems as a diversionary attempt, as a vehicle to pursue aggressive maritime claims. This could sharpen interstate disputes and possibly drive countries towards the brink of outright war. The onus is on governments to limit domestic nationalism.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

3. What are your views on ASEAN-China relations and negotiations over the next 5 years in light of the current China-Philippine conflict (which can possibly be seen as an erosion of the credibility of such negotiations)?

We’re talking here about institutional linkages between ASEAN as a whole bloc with China. In this context, relations have been generally smooth. But the recent South China Sea issue has created rifts within ASEAN. That being case, however, it would not stop ASEAN-China relations from moving forward mainly on the economic and sociocultural fronts. So there’s clearly a bifurcation between economic and security components of this dynamic. As we have seen since the past, ASEAN and China has managed to keep this bifurcation intact, not allowing outstanding geopolitical differences mar the broader bilateral relations.

However, on the security front, the situation has become more intractable. Over the next few years, we would still see ASEAN and China continue with various forms of dialogue and negotiations mainly on the South China Sea disputes, but one should not be too optimistic about the outcome. It could well be a foot-dragging process. Still, I believe generally ASEAN-China ties as far as the South China Sea disputes are concerned would remain stable. Both sides have every incentive to keep the disputes from escalating. At the same time, China and ASEAN would continue to engage each other via the regional architecture revolving around this regional grouping, for example, the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting Plus (ADMM+), focusing on functional, “low hanging fruits” types of practical security cooperation between their agencies.

Still, the underlying amount of distrust towards one another, not least of some ASEAN member states towards China, would limit the extent of this security cooperation. For example, China’s proposal on “early harvest” security cooperation in the South China Sea, even including joint patrols, obtained at best enthusiasm from certain ASEAN member states friendlier to China, but lukewarm response so far from the others.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

4. Most people in our generation have heard about the South China Sea conflict, but do you think you could share more about past maritime security issues in the ASEAN region, and how interconnected are the various disputes in the ASEAN region?

Whenever I have discussions with foreign colleagues from the academia, policy and corporate circles, I explained at length that the South China Sea is neither the primary security challenge nor the defining feature of Southeast Asia’s security landscape. Southeast Asia faces a multitude of maritime security challenges, of varying extent of severity and consequence to each country. Perhaps with the exception of Vietnam and to a lesser extent the Philippines, other ASEAN countries view other forms of maritime security threats as more important than the South China Sea issue. For instance, there is a broader problem of rampant illegal fishing in sub-zones throughout the entire Indonesian archipelago, not just off the Natuna Islands in the South China Sea. Malaysia is more concerned about seaborne militancy off eastern Sabah than the South China Sea disputes. Singapore is worried about maritime terrorism whereas Thailand, about the consequences of slave fishing trade and human trafficking. This is to illuminate the reality that ASEAN member states face more pressing problems than just simply the South China Sea. And threat perceptions do change over time, in ways more uncertain and unanticipated than what would happen in the South China Sea. For instance, when the spate of ship hijacks in 2014 in the lower reaches of the South China Sea and the Straits of Malacca and Singapore have abated, there is a sudden eruption of ship hijacks and crew “kidnap-for-ransom” in the Sulu/Celebes Seas since early this year.

And where interstate maritime disputes were concerned, I believe ASEAN has fared well based on past examples. Back in the 1990s, intra-ASEAN maritime disputes had been a challenge, such as unresolved bilateral maritime boundary issues between Malaysia and Singapore, the Ligitan and Sipadan Islands dispute between Indonesia and Malaysia, just to name a few. But ASEAN member states have closely adhered to addressing these issues based on the rule of law. Where ASEAN as an institution could not help resolve, the member states took those disputes to international arbitration. Notably, the Ligitan and Sipadan Islands dispute was resolved through this avenue and both Indonesia and Malaysia adhered to the ruling. The same goes to the Pedra Branca dispute between Malaysia and Singapore. Even without going to international arbitration, ASEAN member states also demonstrated the ability to reach their own political settlements, for example the Malaysia-Thailand Joint Development Area in overlapping waters in the Gulf of Thailand.

However, there are still unresolved intra-ASEAN disputes, such as the one revolving around the Ambalat energy block off east Kalimantan, disputed between Indonesia and Malaysia. But all existing examples show that ASEAN member states can manage and even resolve their intra-regional problems in an effective way, though not always as smoothly as one hoped to be.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

5. Do you think that the disparity in capacity and (military/monetary) capabilities/resources of the ASEAN countries will create an imbalance in ASEAN maritime cooperation and possibly negatively impact this cooperation?

Certainly to a degree, as I have outlined earlier. Engaging in practical maritime security cooperation goes beyond just espousing a political statement of intent; the country concerned needs to make tangible contributions. Without requisite capabilities and sufficient capacity, it is at times difficult to cooperate. And the extent of contribution does depend also on whether the country involved views this common maritime security problem as more pressing compared to its other priorities.

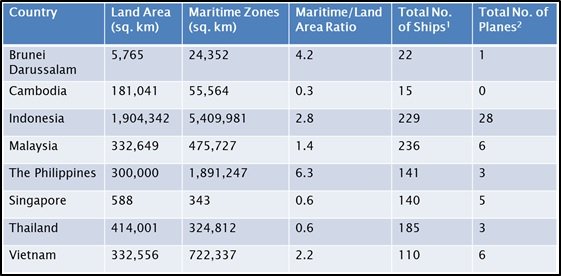

But resource constraints would not be the key determinant of effective maritime security cooperation compared to the broader, intangible issue of lack of political trust. This will not create an imbalance in cooperation to a serious extent. Instead, the more persistent problem comes with the fact that cooperating in a specific area of common interest will mean diverting scarce resources away from other areas. I furnished below Table 1 as an illustration of the magnitude of challenges Southeast Asian countries face in matching their maritime responsibilities with the capacities they possess.

[vcex_spacing size="6px"]

Table 1: Selected Southeast Asian Countries and Maritime Security Capacity Issues

Source: Koh S.L. Collin (2016), compiling various materials including The Military Balance 2015, International Institute of Strategic Studies. Notes: 1. Surface combat and patrol vessels only; includes civilian agencies; 2. Fixed-winged maritime patrol aircraft only; includes civilian agencies

[vcex_spacing size="6px"]

The onus will remain on individual ASEAN member states building their national maritime security capacities in order to cope with as wide and diverse range of challenges at sea as possible, including “going alone” or in cooperation with neighbours.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

6. How do you think ASEAN can promote regional cooperation in maritime security?

It would be easy to say that one way to promote regional cooperation in maritime security would be to put aside historical and political baggage. But it is really easier said than done. The way forward remains challenging and uncertain. The evolution of intra-ASEAN maritime security requires pragmatism: in the context of political distrust, which takes time to overcome, a “building block”, yet less passive or reactive but more proactive, approach to promoting cooperation is preferable. This “building block” approach is gradually incremental in nature, and takes into consideration member states’ willingness and ability to cooperate and contribute to regional resilience.

The most basic standpoint would be to assist individual ASEAN countries to build their own national maritime security capacities. This requires an understanding by extra-regional actors that ASEAN governments prefer to manage domestic issues independently, without the direct interference of outsiders, to maintain regional security but also for domestic stability. Better-endowed ASEAN member states can provide more assistance to ASEAN neighbours, which would allow individual ASEAN governments to better police their own waters and enhance region-wide capacities to collectively deal with common maritime security challenges. This ties in with my earlier point about how effective cooperation is derived from the ability of individual partner governments to contribute tangible physical assets.

The situation would be trickier when it concerns broader, more complex issues related to maritime disputes. ASEAN will remain far from becoming an institution that can arbitrate and resolve outstanding maritime squabbles. It will at best remain a conflict management, not resolution, platform. To do this role effectively, ASEAN will need to continue to adhere to basic tenets of managing interstate affairs on the basis of rule of law. More importantly, member states need to do more to promote cohesion and unity instead of allowing internal rifts to widen and undermine the regional bloc’s utility.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

7. Do you think the ASEAN region is merely an artificial construct, and what do you think has been the true nature of the ASEAN ‘identity’ over the past 50 years?

This is a question I believe best directed as scholars who specialise in international relations, particular on ASEAN studies. While ASEAN is an artificial construct, it is brought together by common, fundamental interests: to pursue cooperation and a strategic environment, conducive for national development. It is not underpinned by an institutionalised framework of rules but a loosely defined set of normative values – the “ASEAN Way” of focusing on inclusivity, consensus, non-interference in domestic affairs of others, etc. That can be considered the “identity” or at least a defining characteristic of ASEAN over the past 50 years.

In a broader sense, ASEAN can pride itself for being the driver of the regional security architecture – an overlapping network of regional mechanisms that bring together not just ASEAN member states but also other extra-regional actors, including Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, Russia, South Korea and the United States. Despite persistent criticisms against this so-called architecture as to its real efficacy, ASEAN’s achievements are noteworthy considering the complex nature of Southeast Asia and the broader Indo-Asia Pacific, in the relatively short time span (since 1967 when ASEAN was first established). Although there is room for improvement, to call ASEAN a mere “talk shop” and dismissing its role in this architecture, in my opinion, neglects the complexities of the region and challenges associated in bringing diverse countries with diverse and at times conflicting interests together in various contexts.

I personally believe that more effort to promote awareness amongst Southeast Asians about ASEAN and its role set in the broader regional and international context is required. Only then can Southeast Asians better help drive policies, shifting this format away from an elite-centric form of decision-making process, towards giving more holism to ASEAN as a construct, imbuing it with a more robust identity and pluralistic nature. I think that a bottom-up (popular-based), instead of top-down (elite-driven), initiatives to promote this awareness would be a right way to go. As such, I feel this ASEAN-Warwick Conference is an interesting and certainly noteworthy endeavour to promote intra-Southeast Asian awareness and understanding through exchange of ideas, and for Southeast Asians to truly take ownership of regional issues that are of consequence to our daily lives.

[vcex_spacing size="14px"]

Contact:

Dr. Collin Koh Swee Lean

Research Fellow, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies

Email: iscollinkoh@ntu.edu.sg

Phone: +65 9820 4735